Chris Marker's Petite Planète

An Instruction Manual for Navigating Culture and History on a Small Planet

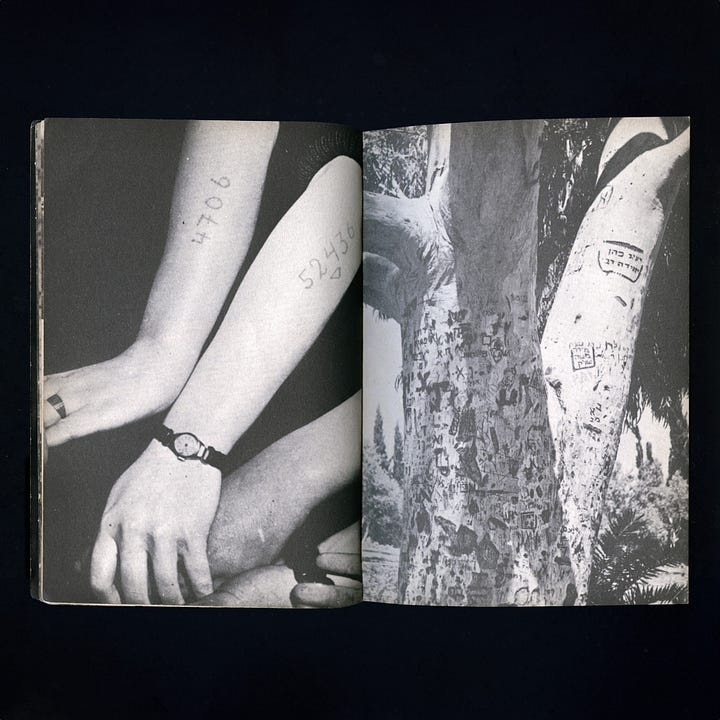

Travel guides often tell you where to go, what to see, and what to eat. But what if there was one that went beyond the surface, challenging stereotypes and bridging cultural divides, all while making you feel like you're in an intimate conversation with a local? The Petite Planète1 series, created by Chris Marker, has done just that. Thanks to Marker's creative vision, the series emerged as a distinctive voice in a world that was still grappling with the aftermath of the Second World War and the onset of the Cold War.

Chris Marker (1921-2012), born Christian François Bouche-Villeneuve, was a filmmaker with a complex career. Far from being just the man behind the camera, Marker was also a poet, writer, editor, graphic designer, political activist, and so much more that it's hard to pin him down to a simple list. Films like La Jetée and Sans Soleil are testaments to his unique narrative style—a blend of fact and fiction, memory and time, all underscored by profound political and philosophical insights.

By the early 1950s, as Marker took his first steps into cinema, he was also working on the Petite Planète series. Envisioned as an “instruction manual for living on a small planet”, the series explored how nations and cultures remember their past and envision their future. Marker's focus on the human element was evident. He encouraged readers to look beyond their preconceptions, urging them to see the world through an unbiased lens. The first issue on Austria was published in 1954 by the French publishing house Éditions du Seuil.

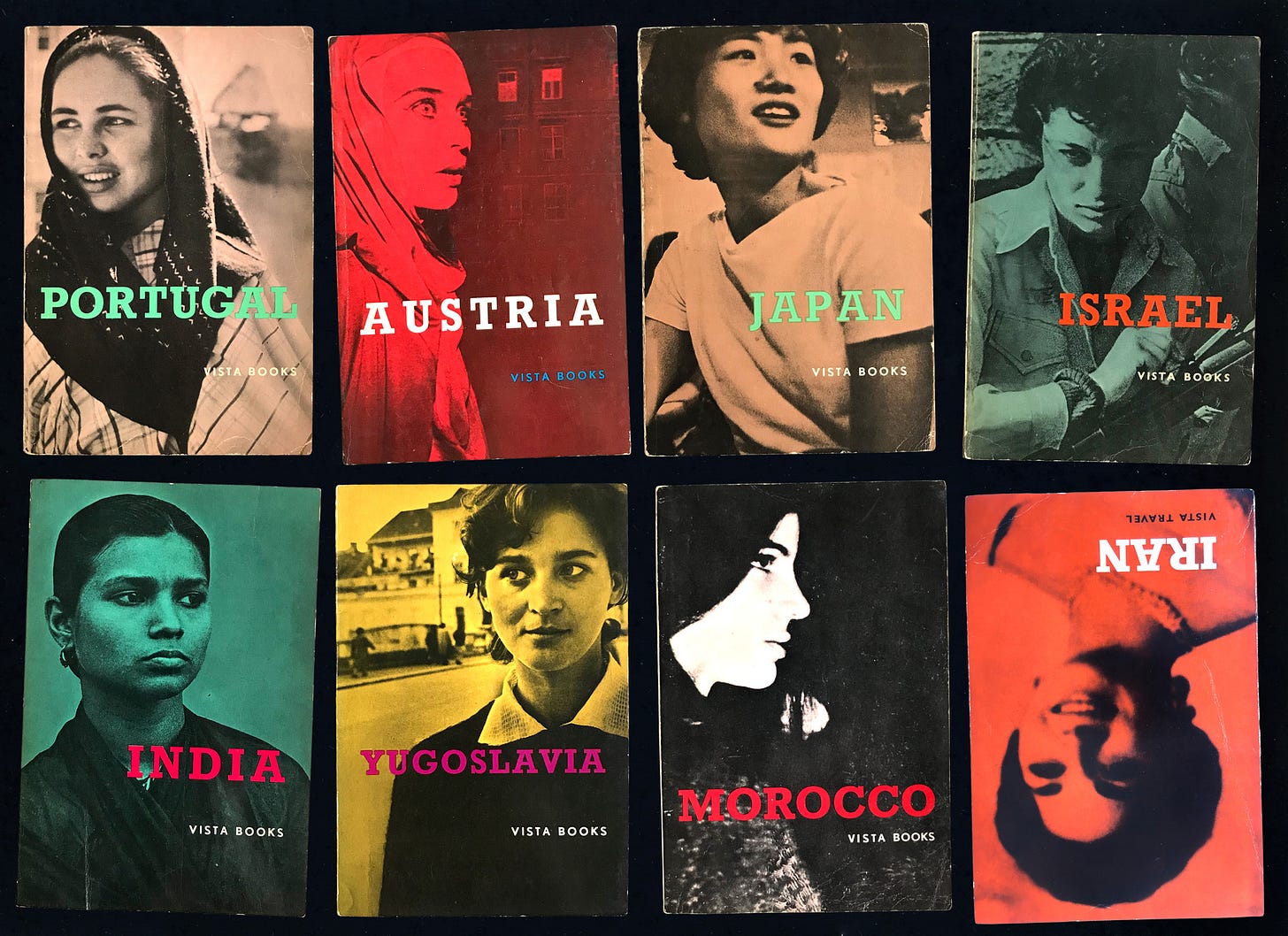

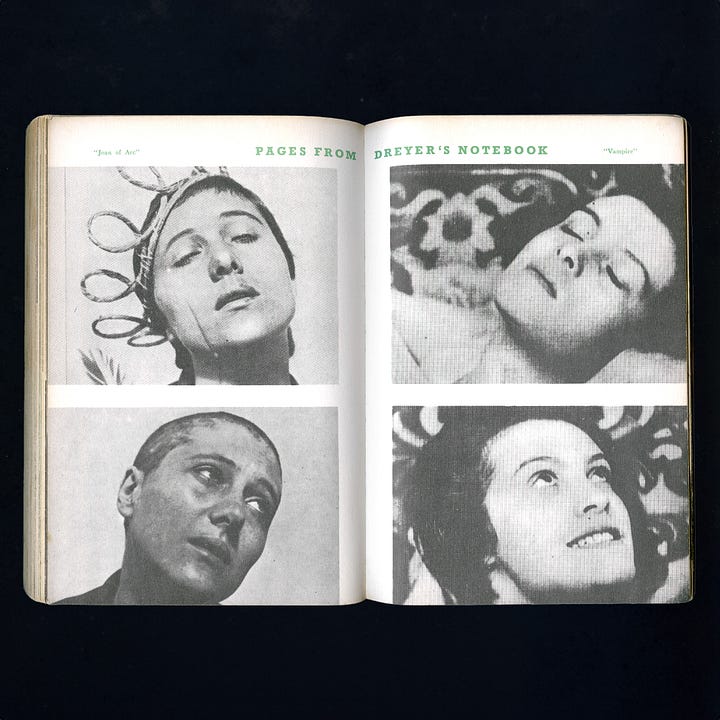

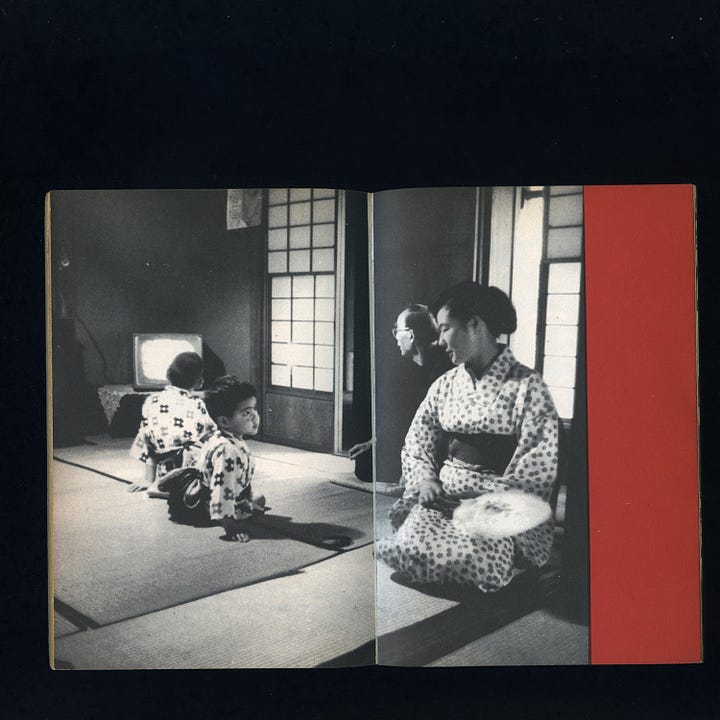

Visually, the series is a treat. Each issue, bathed in a distinct color, showcases a female visage on its cover, echoing Marker's captivation with Carl Dreyer's film The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928). This recurring focus, which runs throughout Marker’s work, is just one aspect of the series' innovative visual design.

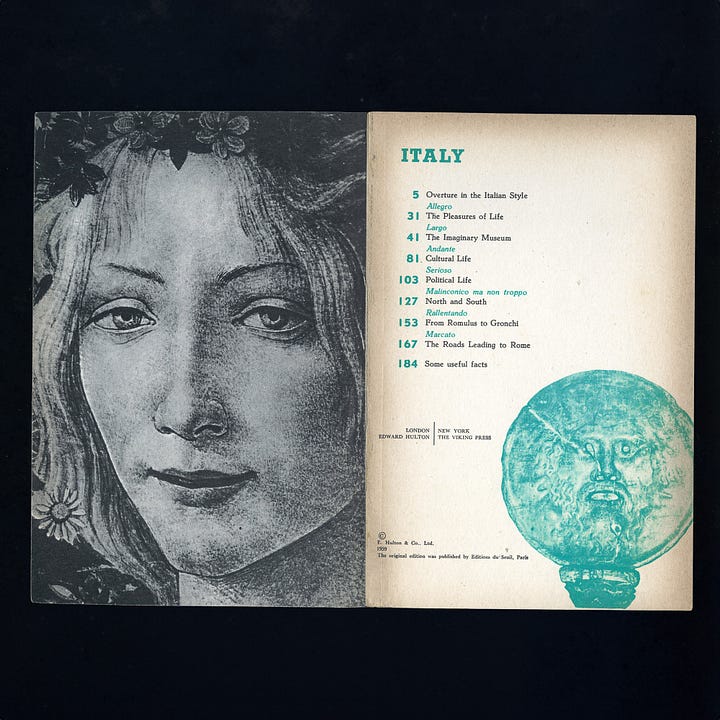

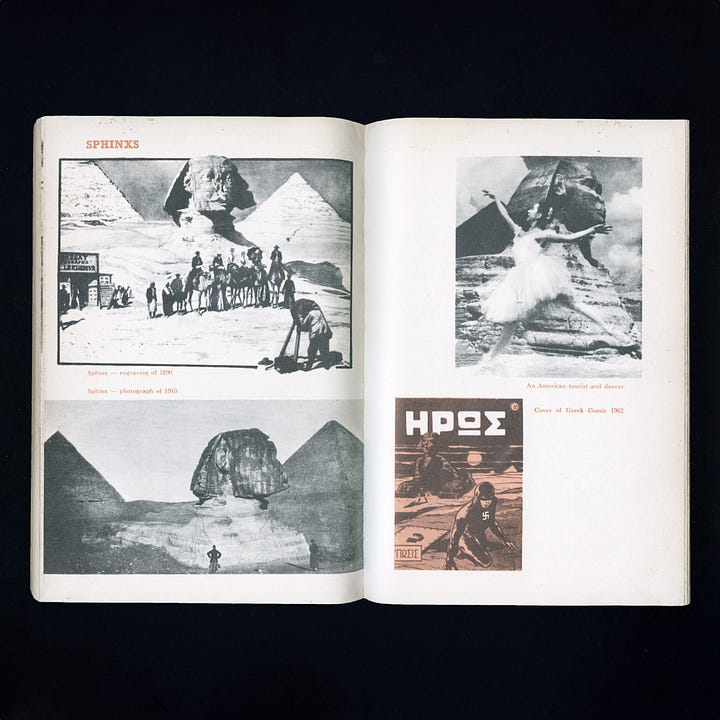

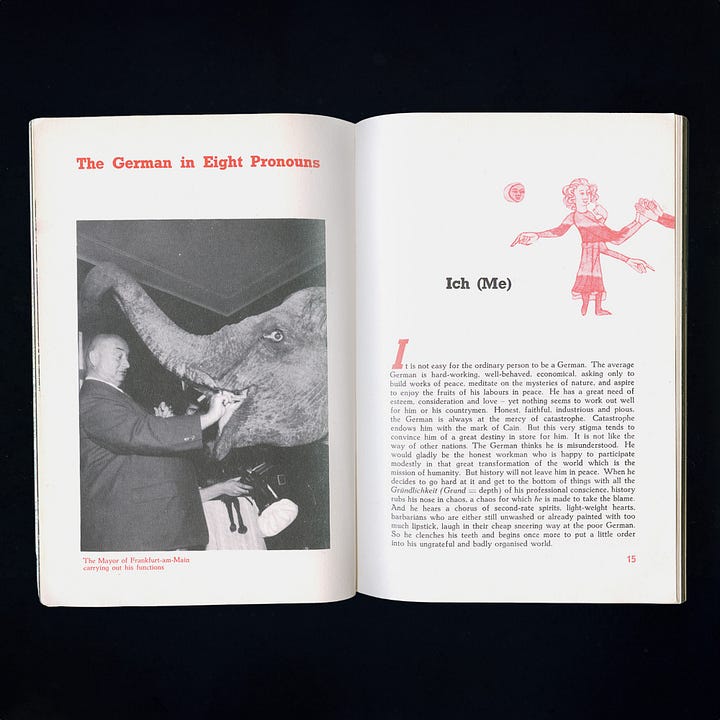

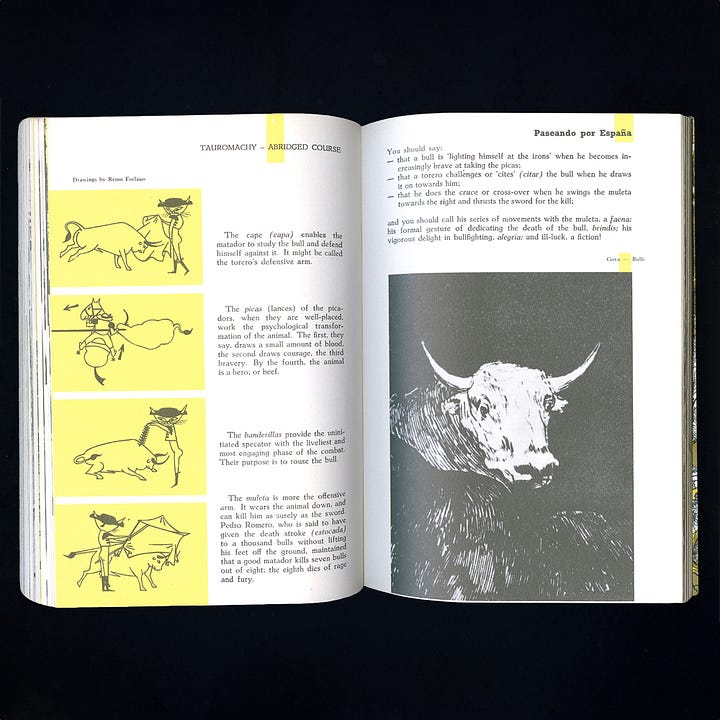

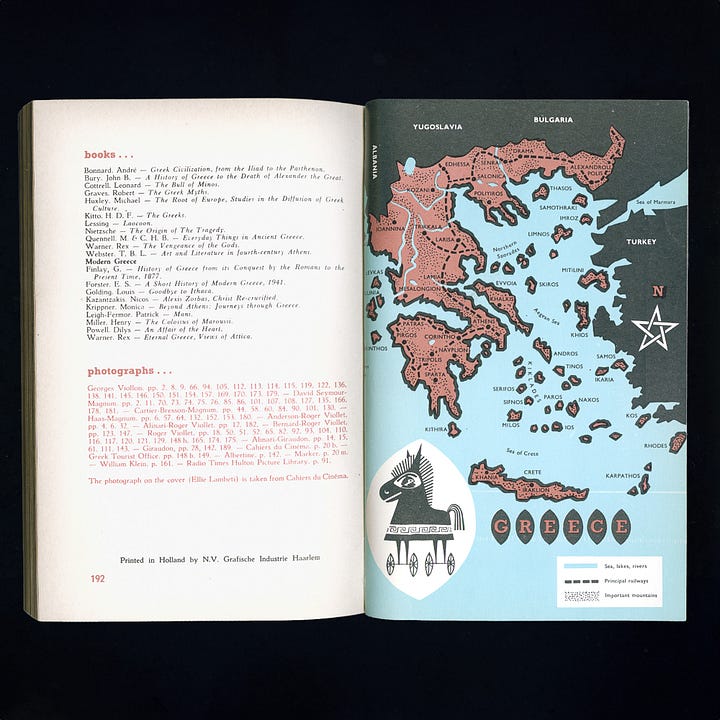

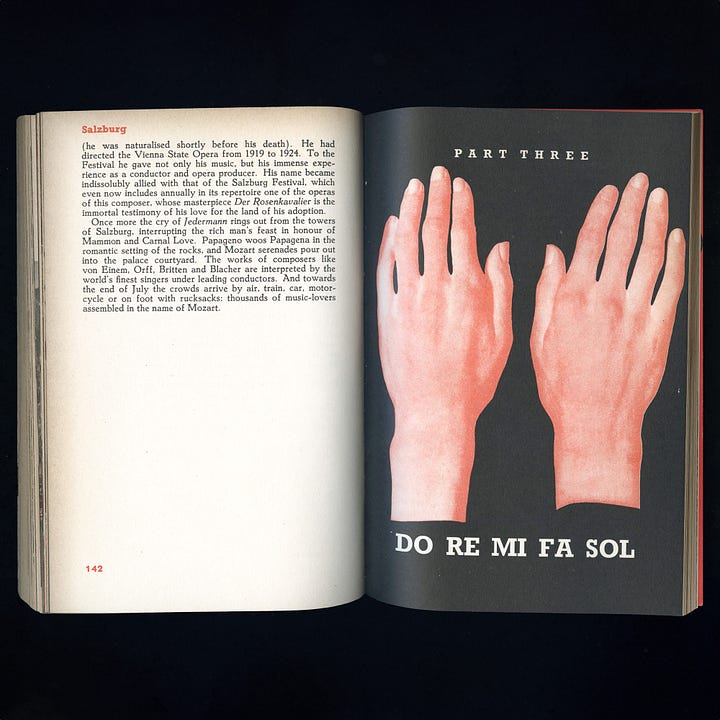

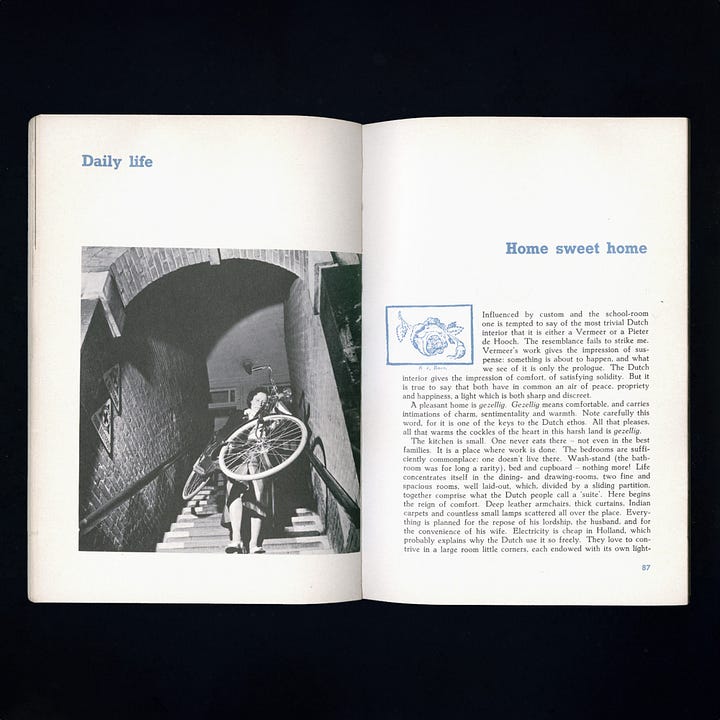

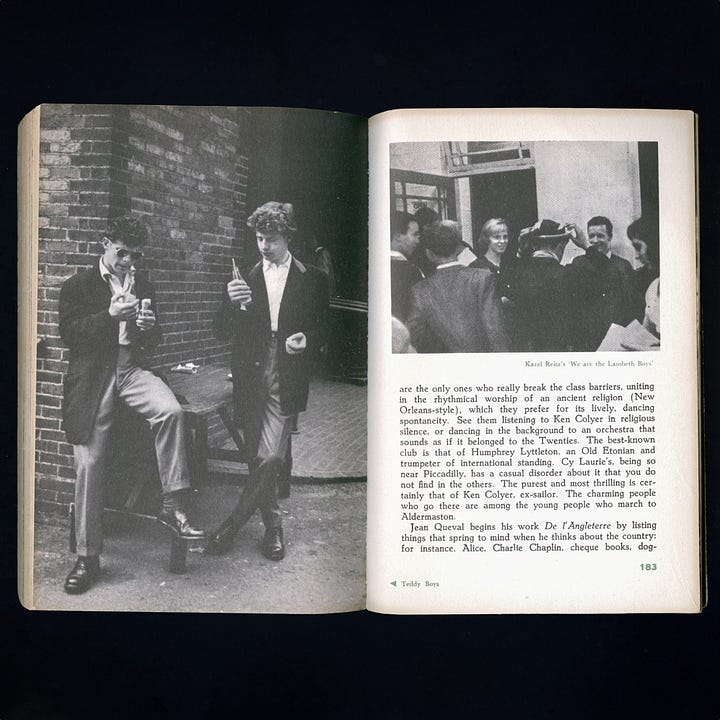

Instead of relying solely on photographs, Marker took a more comprehensive approach to the visual design of the Petite Planète series. He integrated a diverse array of visual elements, ranging from hand-drawn illustrations and graphics to comics and even vintage advertisements. This mix added depth and richness to the narrative, inviting a deeper engagement with the culture and history of each featured country. The layout, credited to both Juliette Caputo and Marker, boldly employed techniques like superimpositions, rotations, and forced cropping. These design choices not only broke away from conventional templates but also redefined the relationship between text and image, adding another layer to the series' avant-garde aesthetic.

Yet, the heart of Petite Planète was its collaborative spirit. Although Marker did not write any of the essays, he believed in the power of collective storytelling. He brought together a diverse group of writers, photographers, and artists who contributed to the series, including Agnès Varda, Brassaï, David Seymour, Elliot Erwitt, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Capa, and William Klein. This collective approach enriched the narrative, offering readers a collage of voices and perspectives.

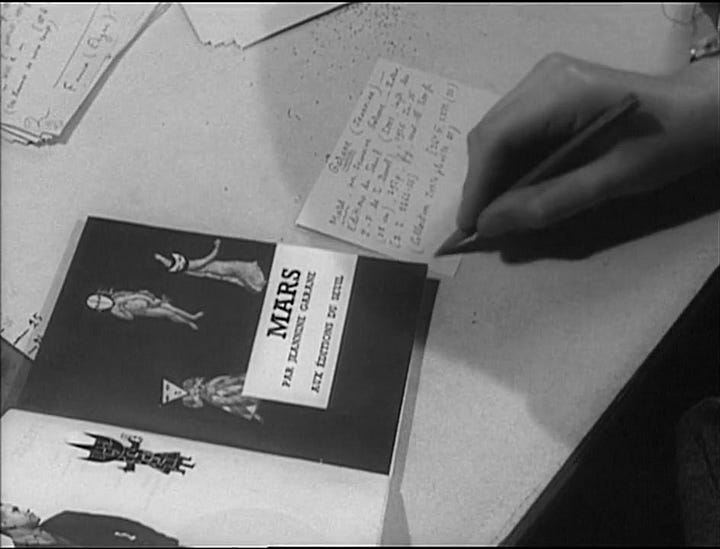

In Alain Resnais's documentary Toute la mémoire du Monde from 1956, the vast corridors of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France come alive, revealing hidden treasures among its myriad of books. One such gem is a peculiar edition from the Petite Planète series titled Mars. This fictional issue, a playful imitation crafted by Marker, showcases his ability to blend reality with fiction seamlessly. The documentary doesn't just stop at this reference; it also subtly weaves in cameos from some of the same contributors who enriched the Petite Planète series, including Agnès Varda, Joseph Rovan, and Juliette Caputo, credited as Giulietta Caputo.

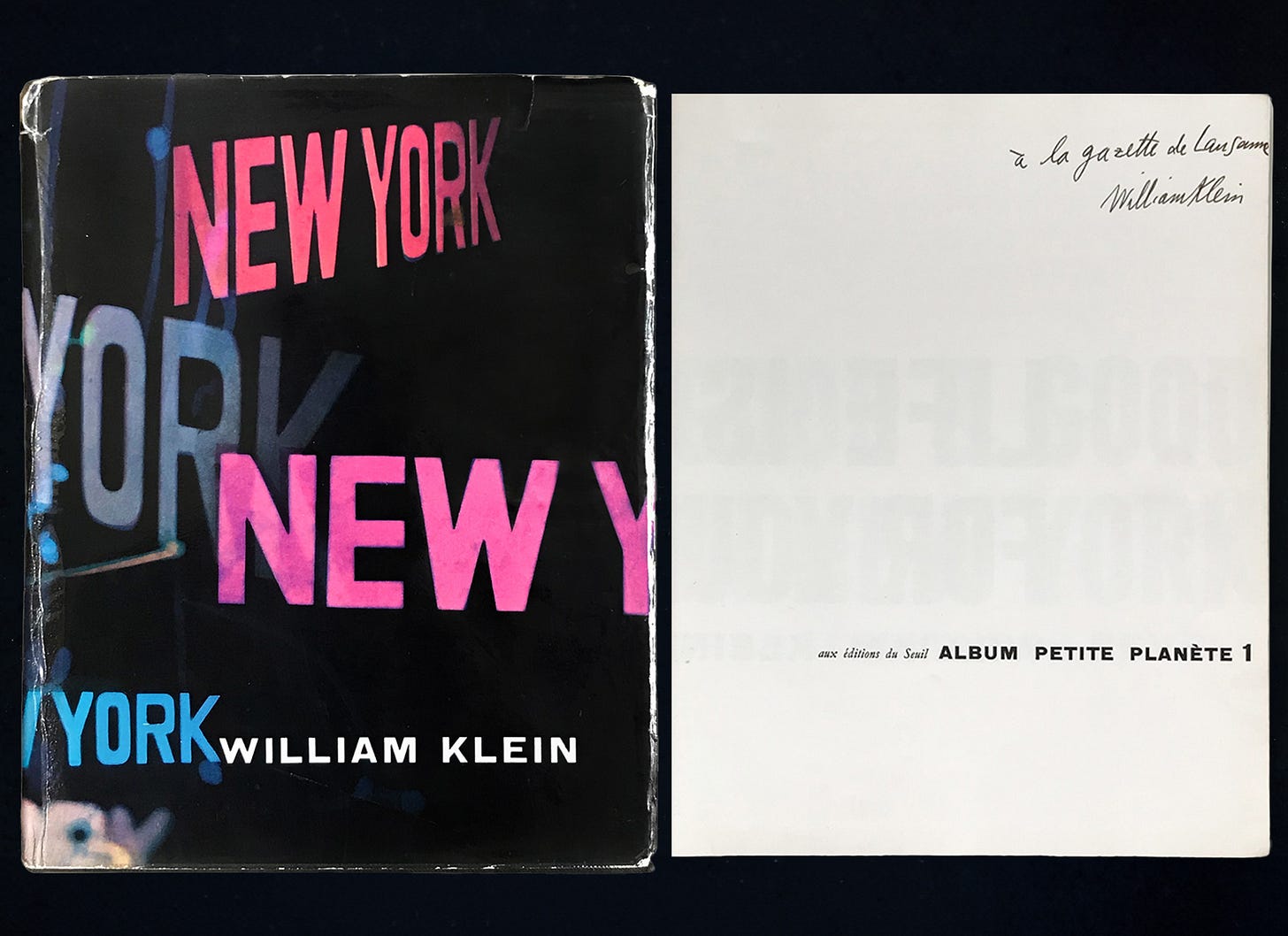

The series' influence wasn't confined to its pages. It played a pivotal role in the publication of William Klein’s influential photo book, Life Is Good and Good For You In New York: Trance Witness Revels2. After numerous rejections in the U.S., Klein, inspired by the Petite Planète series, approached Éditions du Seuil. There, he met Chris Marker, who was an editor at the time. Marker, recognizing the brilliance of Klein's work, became its staunch advocate, going to the extent of threatening resignation if the book wasn't greenlit for publication.

To cater to a global readership, the Petite Planète series was translated into English and published by Vista Books and Viking Press during the 1950s and 1960s. Fortunately, these English editions stayed true to the original design and format, ensuring that the series' unique visual language could be appreciated by a broader readership.

The series didn't go unnoticed by critics and readers alike. Marghanita Laski in The Observer praised it as "... beautifully produced and superbly illustrated with beauty, imagination, and wit." The New York Herald Tribune found them "Brightly written, opinionated, argumentative, and copiously illustrated ... appreciations of the countries." The Times Literary Supplement noted, "Not only handsomely produced, but original in conception, intelligent and lightly written, ... they offer extraordinarily good value." Robert R. Kirsch in the Los Angeles Times highlighted, "An astonishing amount of information and illustration is packed into this new series ... background information for travelers abroad which most guidebooks gloss over or neglect entirely."

Today, where a Google search can instantly transport us to any corner of the globe, the Petite Planète series serves as a compelling counterpoint. It reminds us that the essence of travel isn't just in the “where,” but in the “who” and the “why.” As Marker poignantly noted, “We see the world escape us at the same time we become more aware of our links with it.” While we scroll through endless feeds, Chris Marker's enduring vision nudges us to pause and ponder: What if the real journey is in the stories we share and the connections we make? So, if you're in the mood for an adventure that goes beyond the superficial, why not pick up one of these gems and travel the Chris Marker way?

I would like to end with the opening from the third chapter, The Actor of the Japan Issue from 1962.

Mr. Sato awakes to the rattle and creak of the shot as they are opened. His wife, who rose an hour earlier, has cooked a breakfast of rice, soup, fish - the same as dinner. She serves it while he discusses with his son the subscription to the local judo club or a sailing course which has been started at school. Mr. Sato enjoys talking to his eldest son. It, of course, is not for him to say that his son is intelligent; politeness demands that he should call the boy stupid. But he has a secret affection for him as well as for his two daughters, who are not quite as respectful as they should be; but they often make him laugh. At this moment they are giggling madly at the kitchen sink with a cousin who has come up from the provinces to have her tonsils removed (gratis) by a school-friend of Mr. Sato. This friend's specialty is plastic surgery, and he is making a fortune by enlarging eyes for girls who want to make themselves beautiful.

The girls are making rather unsuitable remarks about this surgeon, and their mother expresses her disapproval in no uncertain terms, to the great regret of Mr. Sato. The grandmother in the back room lets out a groan - without any special reason, except to remind everyone that she is there. The maid who had been sent for twenty yen's worth of sugar, comes back with horse-radish. Cries of protest, jeers: the maid, a new girl from the country, breaks into loud sobs. The baby son, who has been asleep, wakes up yelling. The daughters, rushing past, jostle Mr. Sato who was opening the Yomiuri, one of the three papers he reads every morning. He grumbles; but he realizes the limitations of his own authority. What could he do without appearing ridiculously tyrannical? By intellectual conviction, or - who knows? - by temperament, Mr. Sato dislikes tyranny. He does not answer Mrs. Sato's 'Jeremiads', although a little firmness, a gentle recall to her duty of patience might not have done any harm. He rises, slides the paper door in which the children have made another hole, and shuts himself up in the lavatory. What a haven of peace! He is alone. It is the only place in Japan where one can be alone. A tiny room, kept very clean; no seat, only a hole in the floor. In one corner, a flower tastefully arranged in a vase. Mr. Sato reflects on a book he has just read, in which the author praises the dark corners of Japanese houses in poetic terms. Indeed, the chiaroscuro here is just what Tanizaki describes. Little light filters through the ground glass of the windows, and it is hard to read the paper. But Mr. Sato decides that this Tanizaki is a crypto-reactionary. So many others, authors and artists, go that way after having been innovators, even revolutionaries in their youth. When aging and famous, they seek comfort and stability. Their boldness ripens into staid wisdom, and that wisdom is patriotic.