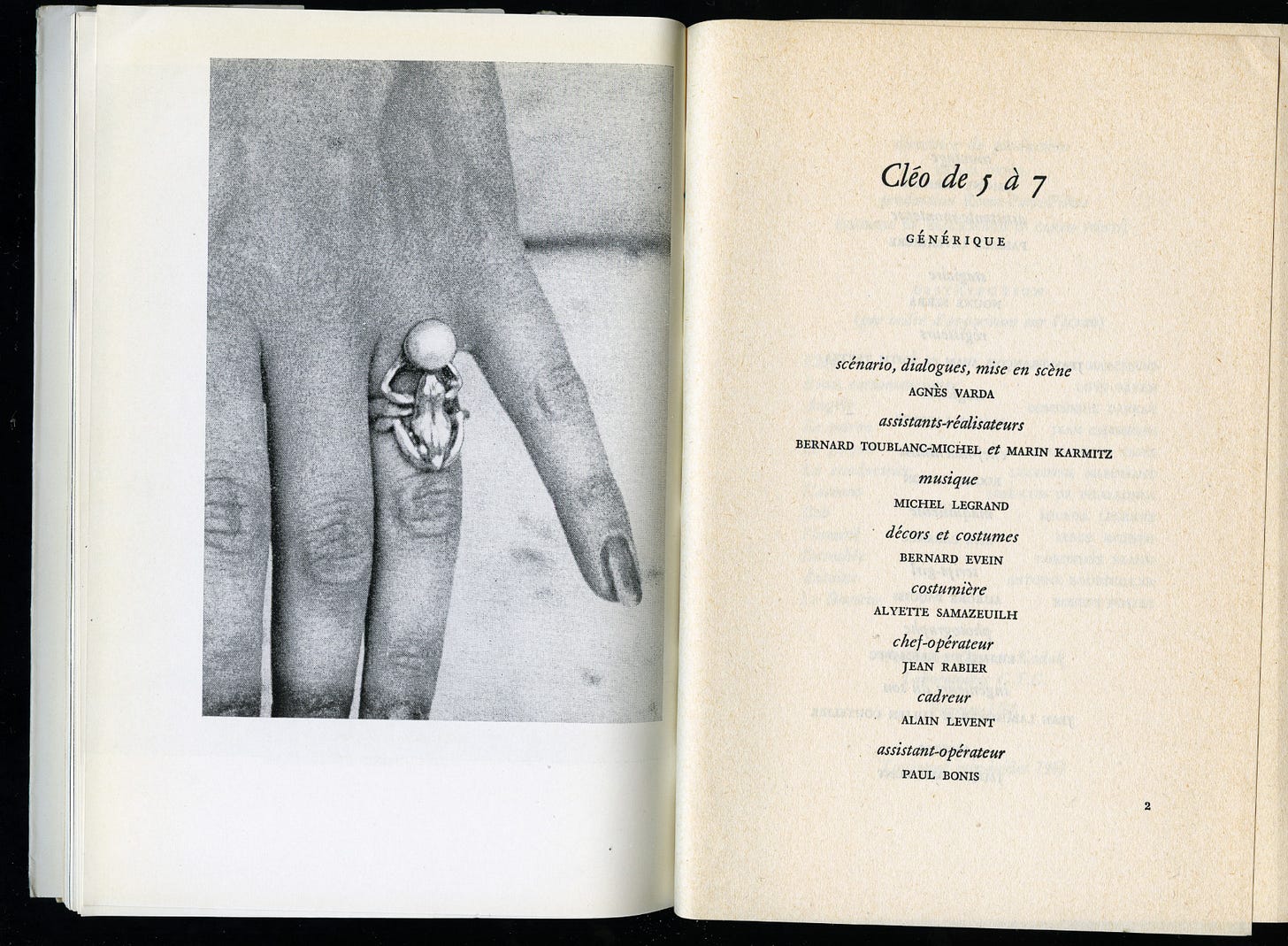

Agnès Varda

Cléo de 5 à 7 – feat. Rainer Maria Rilke, Denis Diderot, Gustave Flaubert, Hans Baldung Grien, Cléo de Mérode, and Leonor Fini

Welcome to the first issue of the Chunking Books newsletter!

In this newsletter, I will be sharing new exciting books from my catalog and taking them as a starting point to explore the many stories that books can tell beyond their content.

As a bookseller, I am always interested in how stories connect and influence one another. Each work tells its own distinctive story, but in conjunction with other works, it can offer new insights and create a dialogue that spans time and artistic mediums.

I thought Agnès Varda’s work would be best suited to kick off this newsletter, as she so masterfully blends literature, visual art, and popular culture.

I hope you enjoy it.

Sören

A Diffuse Fear of the Big City and its Dangers – featuring Pier Paolo Pasolini, Rainer Maria Rilke, and Denis Diderot

Only a few films can match the cultural impact and critical acclaim of Agnès Varda's Cléo de 5 à 7, one of the most important works of the French New Wave. Its powerful portrayal of mortality and identity has captivated viewers for decades, yet the film's origins and influences have received comparatively little attention. It is time to highlight some of the works that contributed to the creation of this cinematic masterpiece.

The film was actually born out of necessity, as Agnès Varda's initial project, a color feature film titled La Mélangite, couldn't get funding for its planned production in Sète and Venice. Georges de Beauregard, the producer behind Jacques Demy's Lola and Jean-Luc Godard's À bout de souffle, suggested to Varda that she should make a small black & white film instead, which shouldn't cost much money. She took on the challenge and ended up shooting in Paris, intentionally limiting the number of sets and locations in order to keep expenses down.

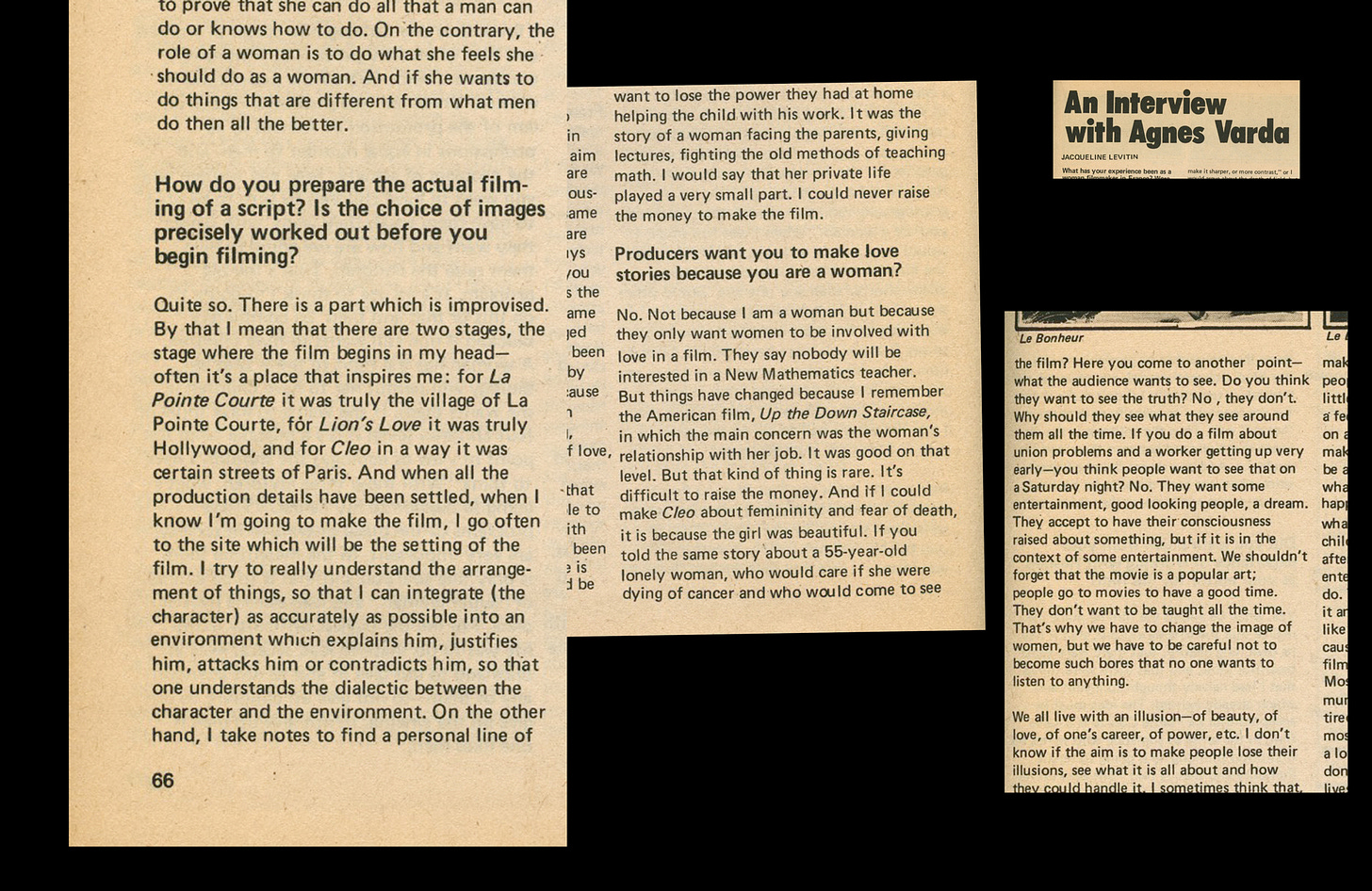

In an interview with Women & Film magazine from 1974,1 Varda was asked how she prepares for filming a script:

What was it about the streets that inspired Agnès Varda? In her book Varda par Agnes, she recounts her move to Paris from the countryside in the 1940s and how she felt “a diffuse fear of the big city and its dangers, of getting lost alone and misunderstood or even being bumped into”.2

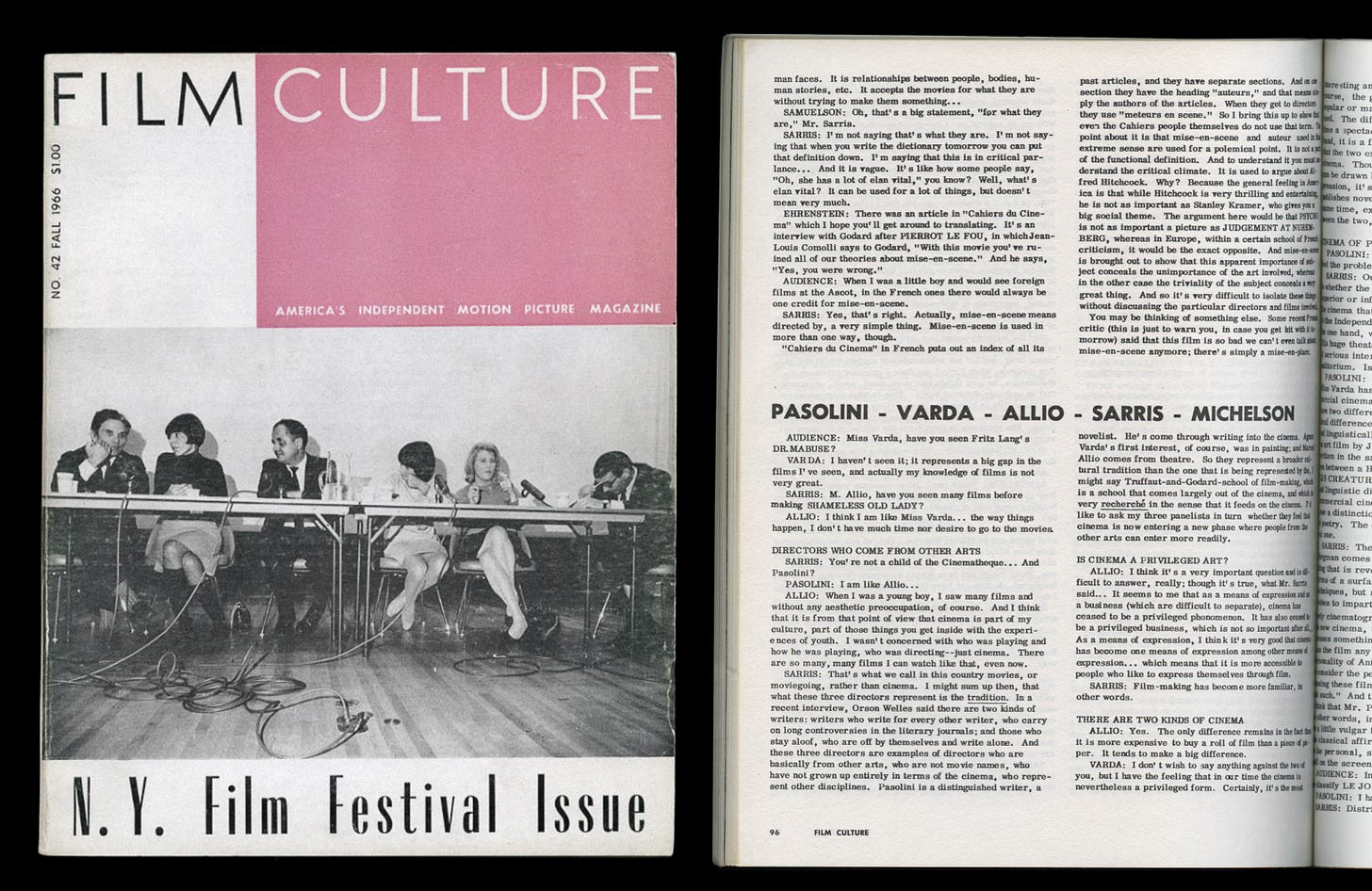

In 1966, Agnès Varda and Pier Paolo Pasolini participated in a panel discussion at the New York Film Festival, where they discussed, among other things, the power of images in cinema. Their conversation was later published in Film Culture magazine,3 with an interesting statement by Varda, in which she said that cinema should prioritize the emotional impact of images over philosophical theories:

Pasolini: (To a question about existentialism and cinema) The cinema, like the cinematographic rhetoric says, is more than anything visible, it’s images. The connection with the visible world is closer, more personal, more emotional, than in any other art.

Varda: I’m not interested in the philosophical theories of Satre. My interest is the specificity of cinema - - that which is really important to cinema. If an image is meaningful, as they say in critical parlance, perhaps one has to use it, but that’s already a bit theoretical. What’s really important is to have an intense (violent) feeling for images. The real problem is to use images which represent something for you personally, which has a certain strength. Afterwards you can in a sense discover meaning, but what happens is that the image in a sense carries through its own force - - and creates its understanding.

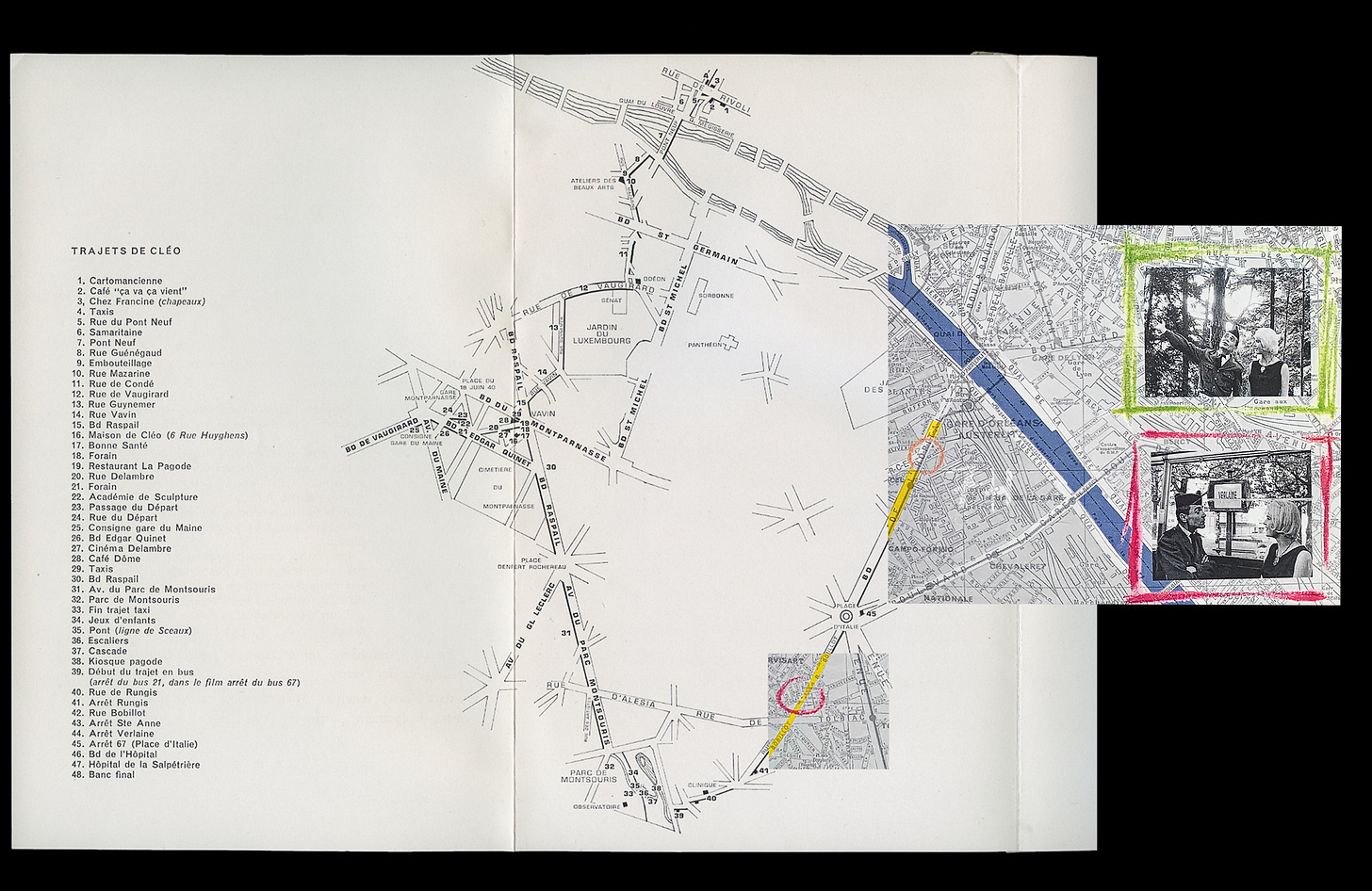

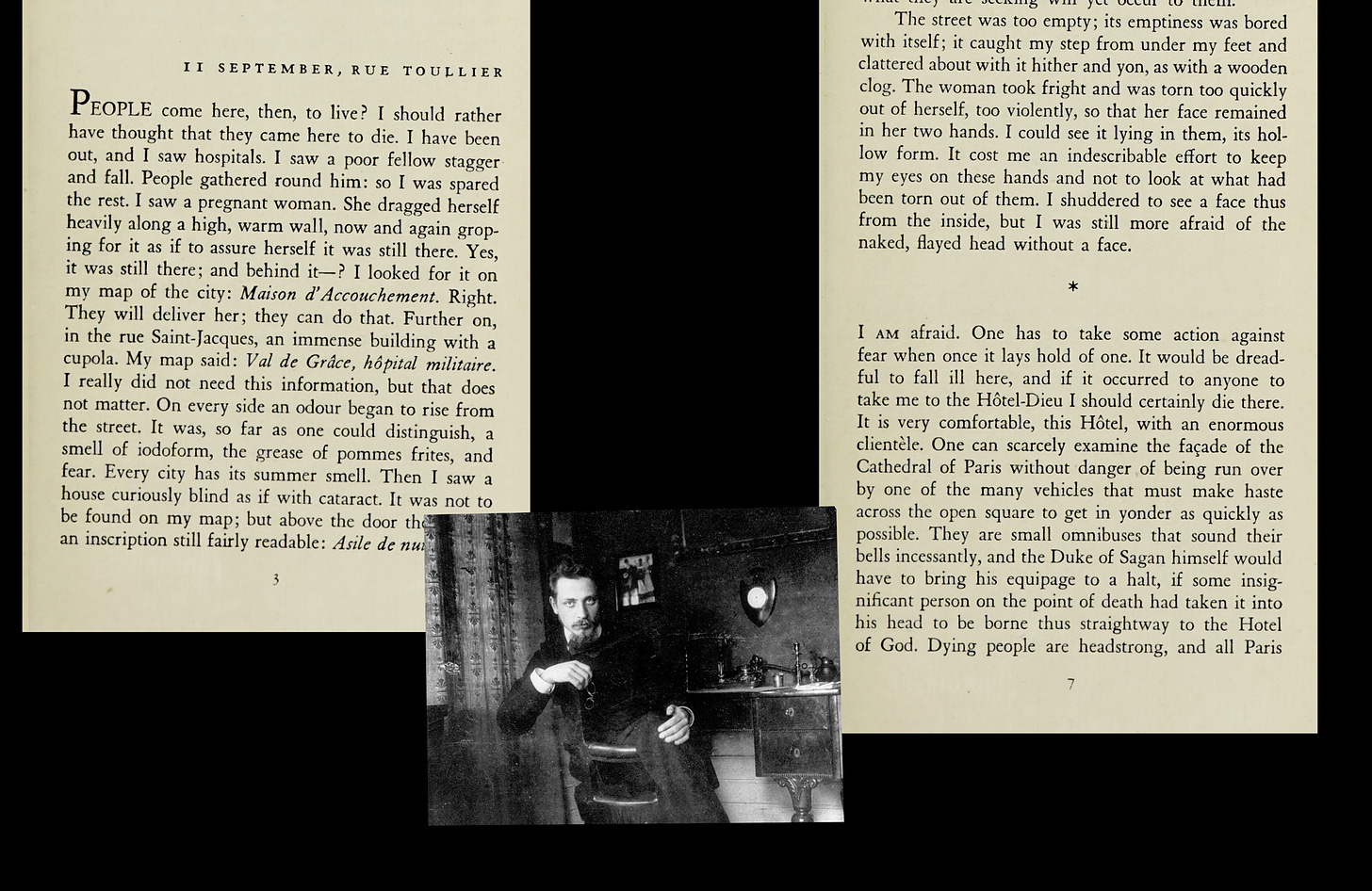

Back to the fears of the big city: Varda's fears of Paris reminded her of the ones described by Rainer Maria Rilke in his 1910 novel The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge.4 Rilke processed his own experiences living in Paris through his novel, exploring themes such as death, fear, poverty, fate, and identity. This, in turn, had inspired Varda to create those unique street scenes in Cléo de 5 à 7, which were set in the same neighborhood where Rilke's protagonist, Malte, wandered.

Agnès Varda reshaped these fears into a single, dominant fear of cancer that took root in people's minds during the 1960s. Inspired also by Denis Diderot's Jacques the Fatalist, she imagined a character wandering through Paris grappling with the fear of cancer.

In Diderot's anti-novel, Jacques and his master travel through France exchanging anecdotes and discussing philosophical questions on fate and free will, similar to the themes explored in The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge. Both works question how much control we truly have over our own lives and use innovative narrative techniques that challenge conventional notions of storytelling. Varda shared a similar approach, by weaving together fictional and documentary elements in the film and experimenting with objective and subjective time. The master was now a singer, accompanied by a fatalistic servant.

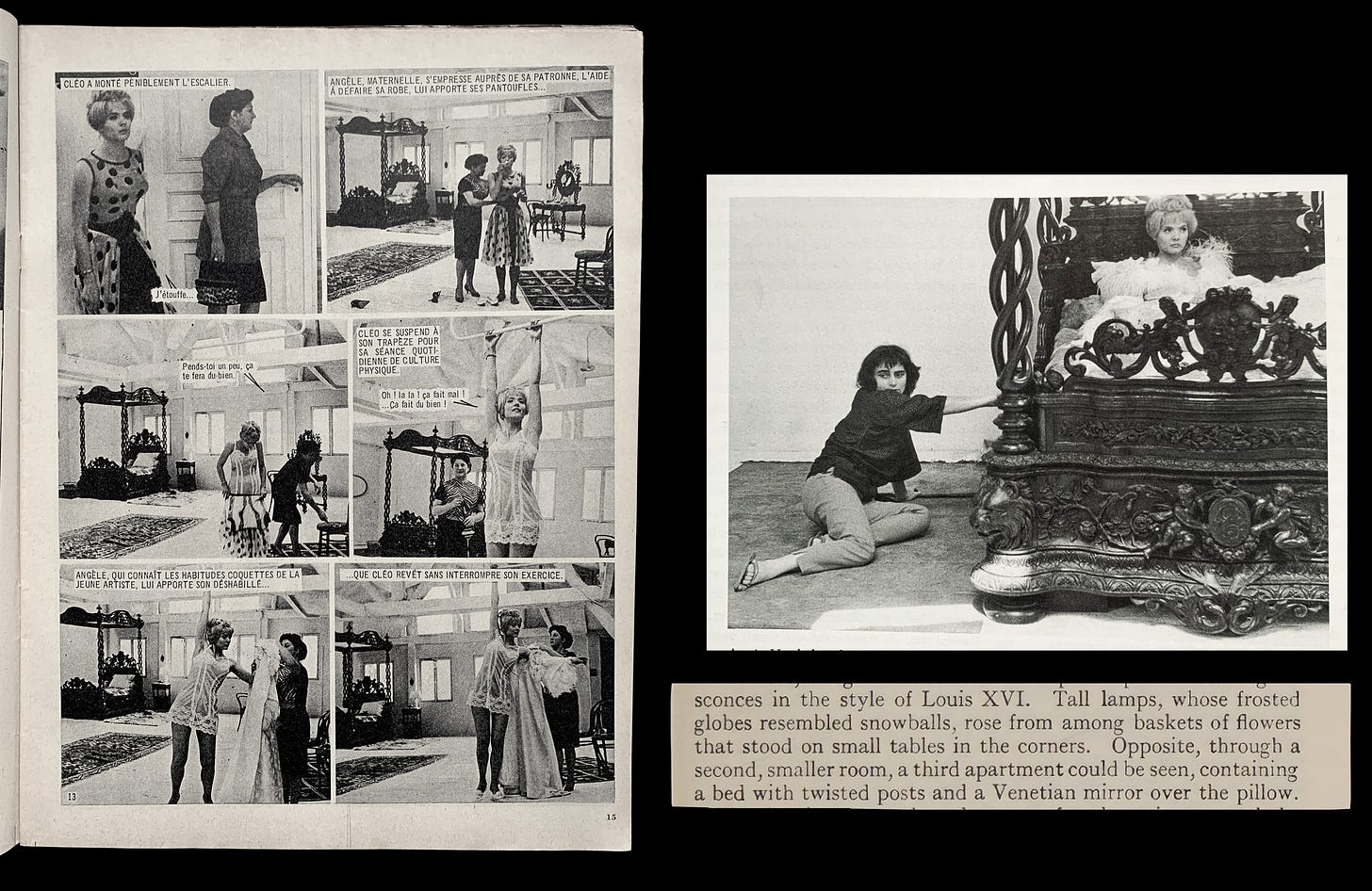

Death and the Maiden – featuring Hans Baldung Grien, Cléo de Merode, Leonor Fini, and Gustave Flaubert’s Rosanette

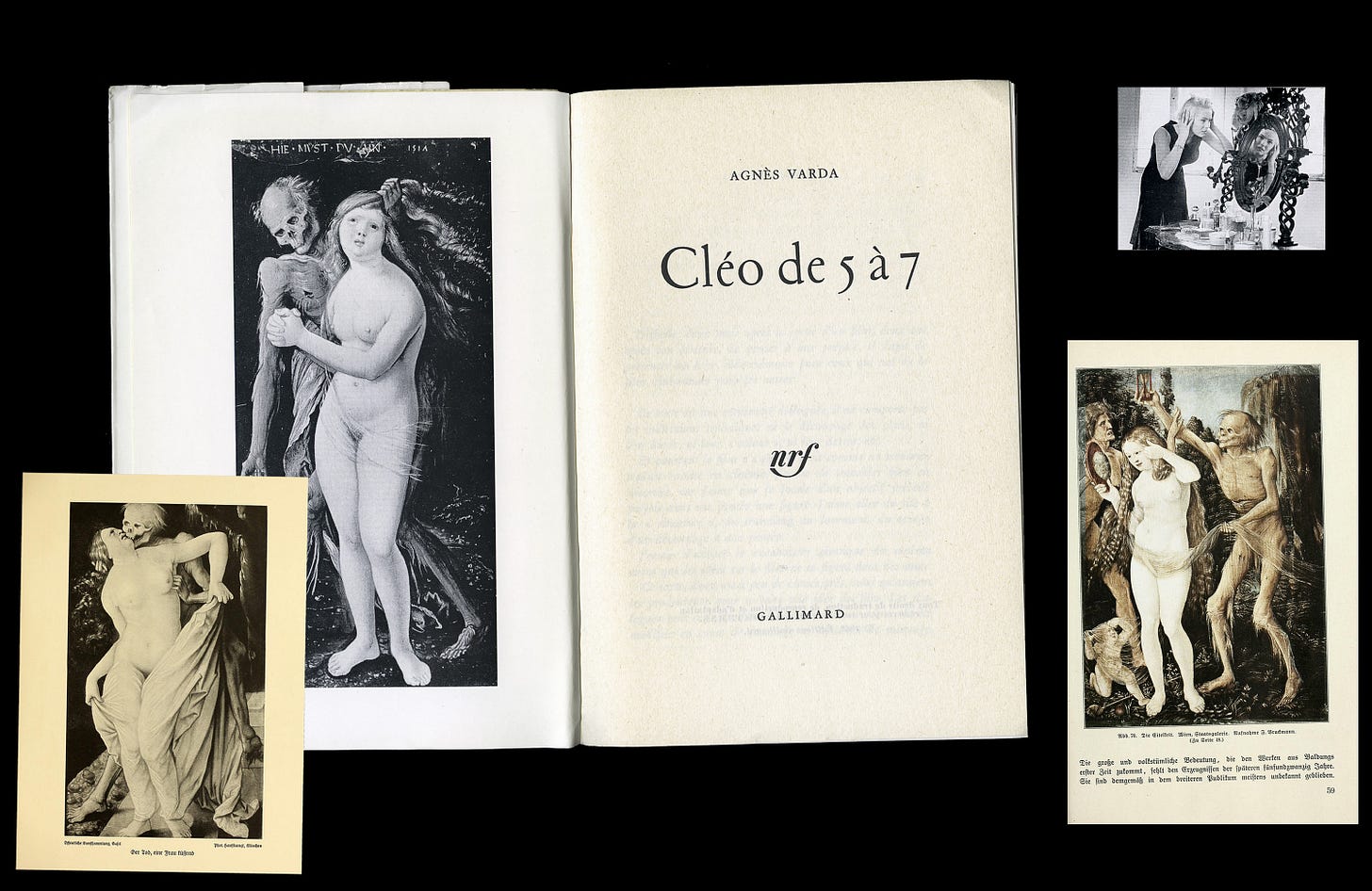

While writing the script, Agnès Varda was constantly drawn to a particular image of a beautiful woman being embraced by death, represented by a skeleton. It was the painting by the German artist Hans Baldung Grien entitled, Der Tod und das Mädchen [Death and the Maiden] from 1517. Baldung Grien was a student of Albrecht Dürer and dealt very extensively in his work with Eros and Thanatos, the connection between desire and death. Varda built on this allegory to effectively capture the fear of cancer and mortality that runs throughout the film.5 The motif of Death and the Maiden was quite popular in the Renaissance, particularly in Germany, and was revived during the Romantic era through Franz Schubert's String Quartet No. 14, also known as … Der Tod und das Mädchen.

Le Petite Fille [The Little Girl], adorned and admired like a carefully dressed doll, but then left alone with her fears and insecurities, was originally intended to be the title of the film. It was the leading actress, Corinne Marchand, who introduced Agnès Varda, to the famous, versatile dancer and socialite of the Belle Époque - Cléo de Merode.6

At the end of the 19th century, affordable photographic reproductions paved the way for the ballerina from the prestigious Paris Opera to be elevated into a worldwide symbol of beauty and glamour. Cléo de Merode's portrait was widely reproduced on postcards, in popular magazines, and sold in stores around the world, making her one of the first global icons of pop culture.

Vardas Cléo, tall and blonde, embodies a different but familiar concept of beauty. The film, however, centers on the moment when she claims her independence and refuses to be objectified. She discards the symbols of her cliché, including her wig and feathered dress, and regains control of her own identity. As she steps out onto the street again, her role shifts from being the looked-at object to the looking subject.

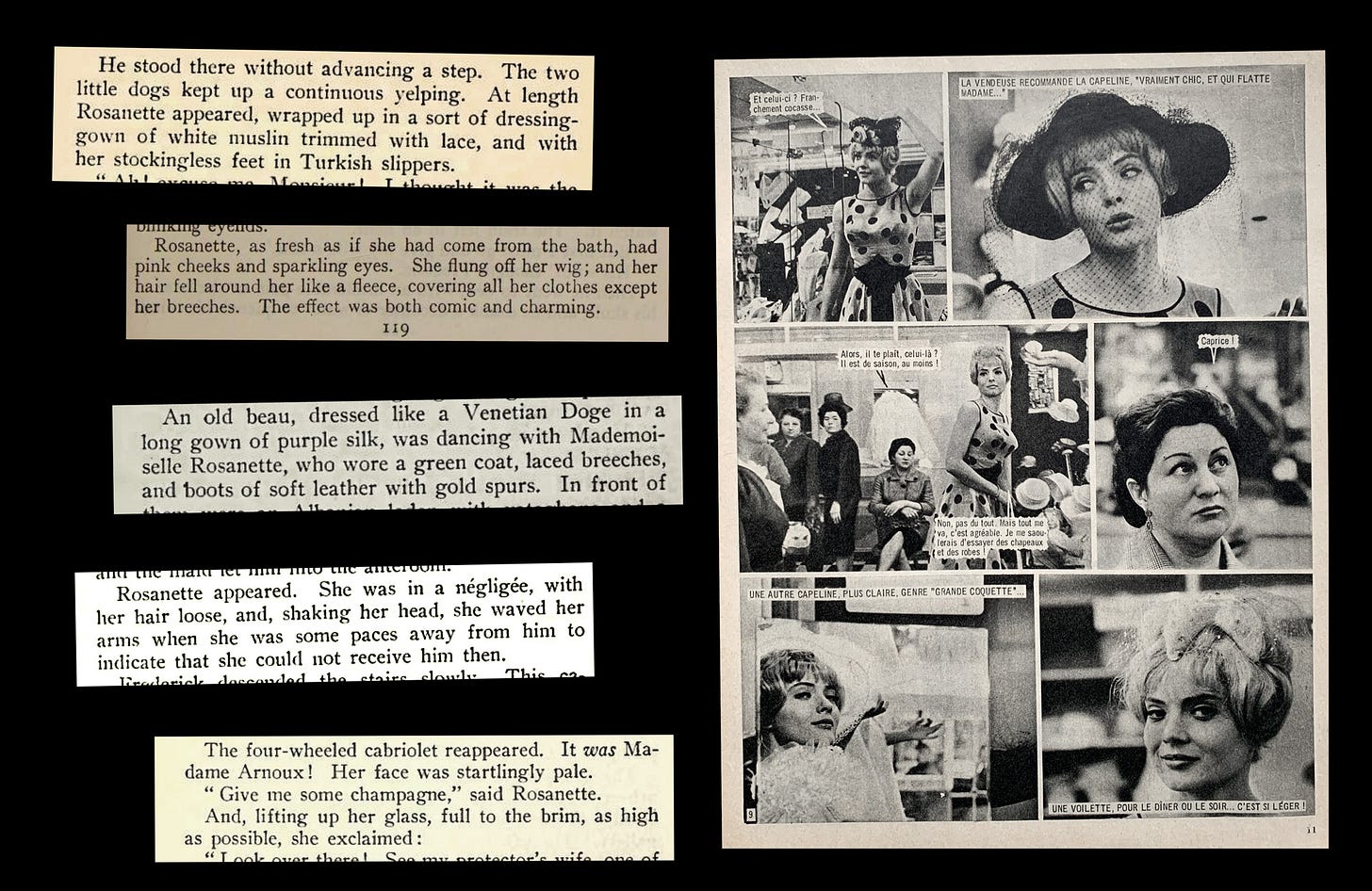

Many influences shaped the character of Cléo, which refers to both real people and fictional representations. A notable source of inspiration was the surrealist painter Leonor Fini, as well as the character of Rosanette in Gustave Flaubert's novel Sentimental Education.

I found Angès Varda's creative process incredibly fascinating and I'm always amazed from which sources she has drawn inspiration. The next newsletter will pick up where this one left off and if you are interested in the books featured in this newsletter and would like to see more of Agnès Varda's work, please feel free to visit Chunking Books.

You can see all books on Agnès Varda HERE.

Thank you for reading!

Analyse passionnante et richement illustrée !

Bravo !!

Serge Zreik

zk.images