The story of Lou Scheper-Berkenkamp and her children's books

The remarkable life of one of the first women to study at the Bauhaus.

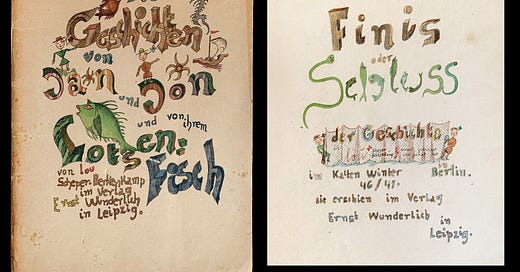

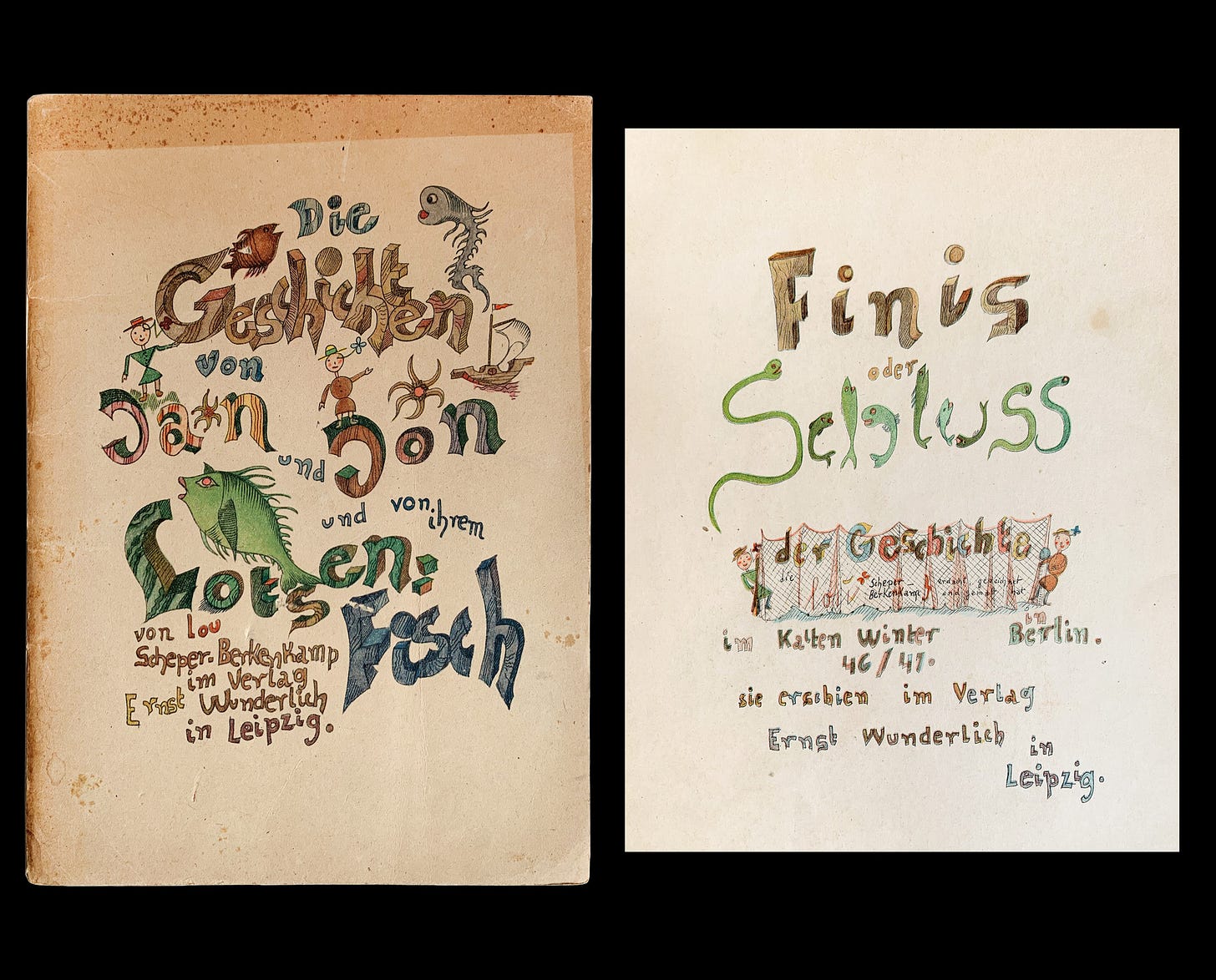

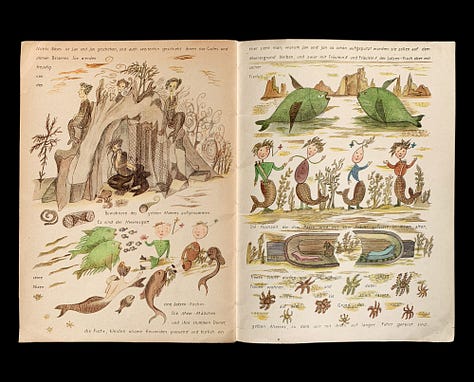

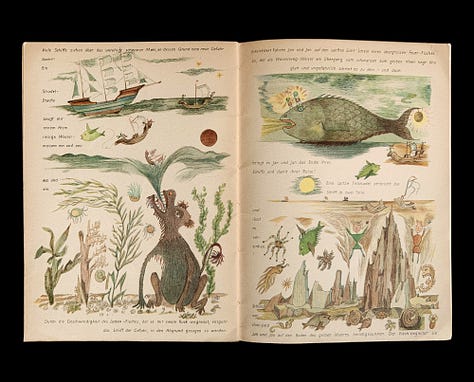

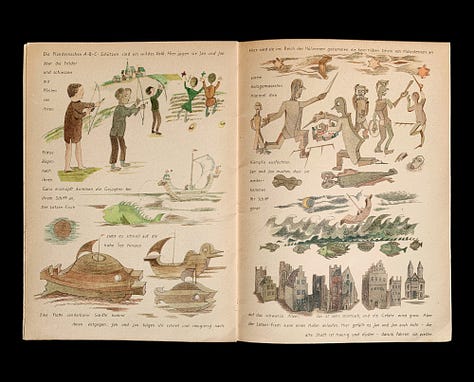

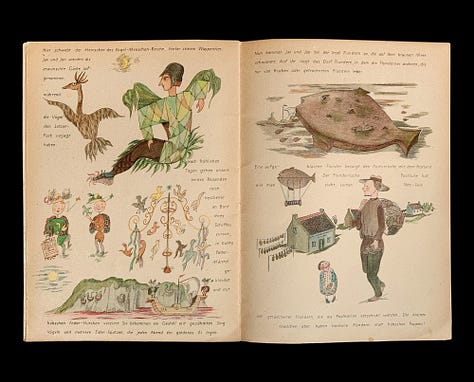

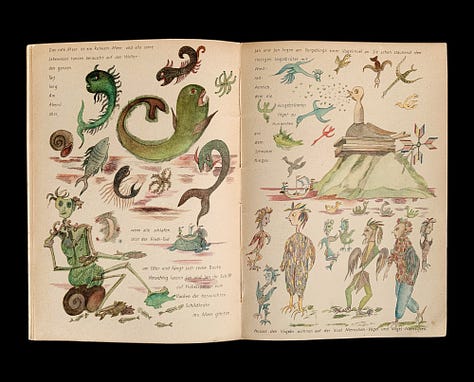

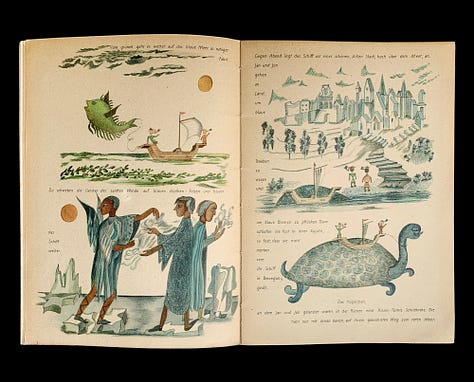

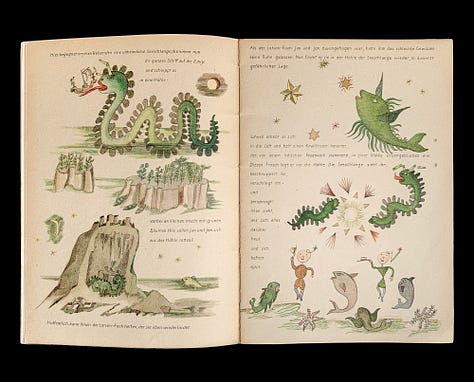

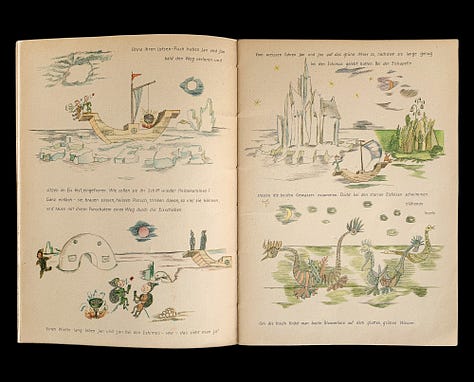

When I first picked up Lou Scheper-Berkenkamp's Die Geschichten von Jan und Jon und von ihrem Lotsen-Fisch, I was immediately drawn in by the stunning fusion of colors, shapes, and text. The book effortlessly wove together contemporary and classic elements and left me with a deep sense of connection.

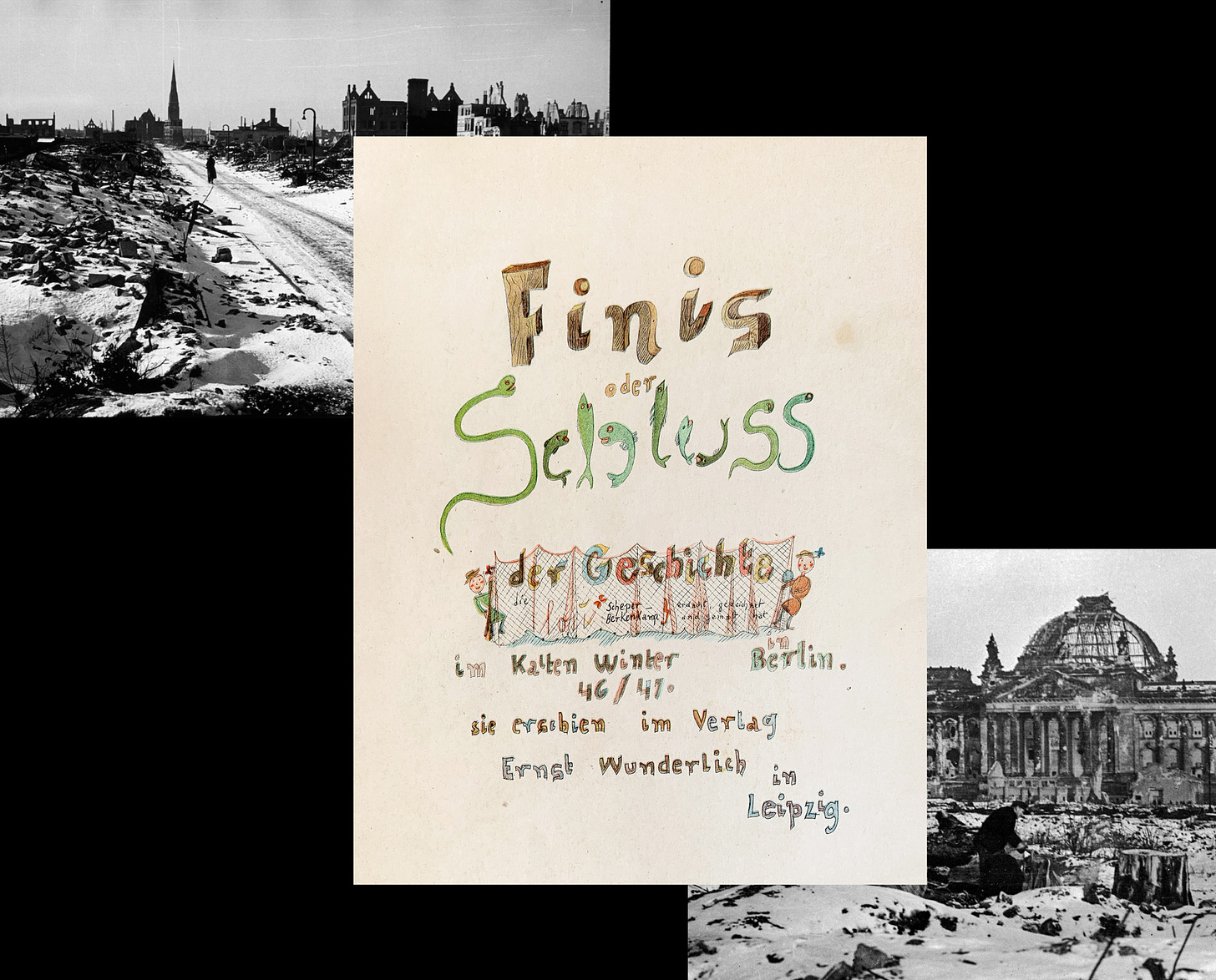

As I flipped to the last page, a small note above the publisher's name caught my attention: “from the cold winter of 46/47 in Berlin”. This detail stayed with me and made me wonder about the challenges faced in publishing a children's book in post-war Berlin. Curious, I dug deeper and discovered that the story behind the book was as fascinating as the book itself.

Lou Scheper-Berkenkamp was among the first women to attend the Bauhaus, but put her artistic ambitions on hold to support her husband's career and raise their three children. She lived through the rise of the Nazis, the forced closure of the Bauhaus, World War II, and despite all of this, played a part in the cultural rebirth of post-war Berlin.

I. Lou Scheper-Berkenkamp

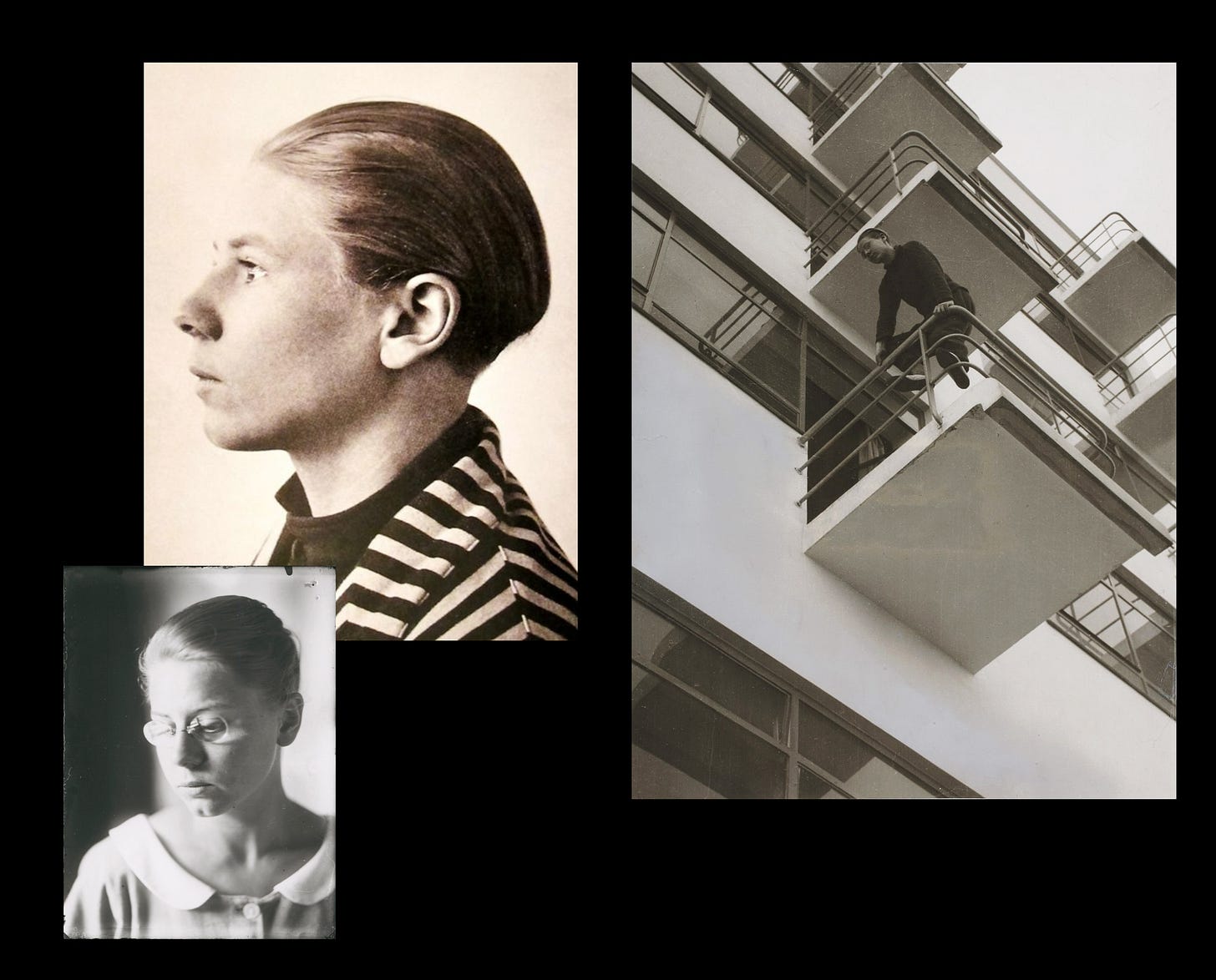

Born in Wesel, Germany in 1901, Lou Scheper-Berkenkamp attended the Bauhaus between 1920 and 1923, taking classes with Johannes Itten, Paul Klee, and Wassily Kandinsky. Despite women often being restricted to so-called "female arts" such as weaving or interior design, Lou carved out her space in the workshop for decorative and mural painting. It was there that she met her future husband, Hinnerk Scheper, who led the workshop alongside two fellow students and developed an innovative color concept for modern architecture.

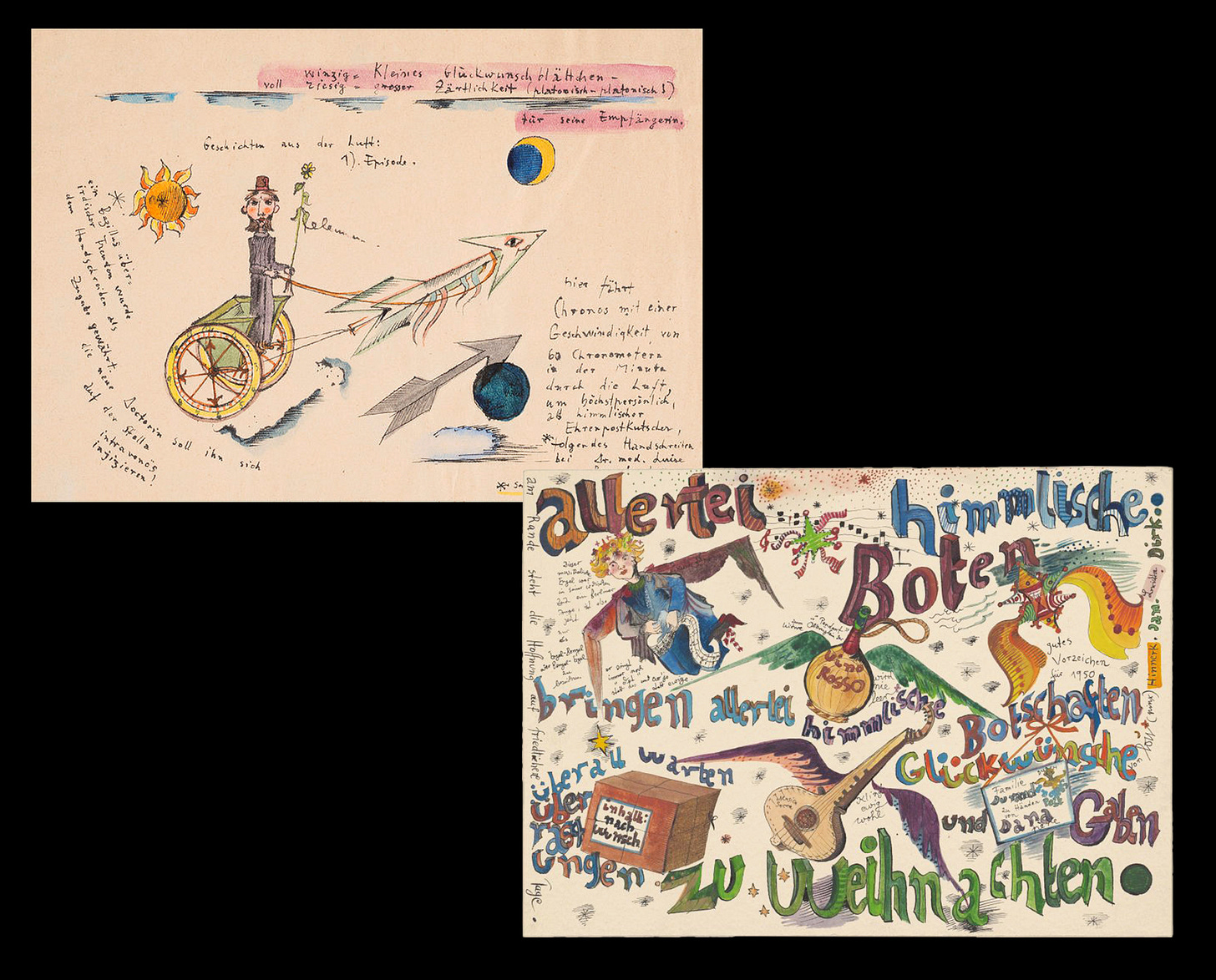

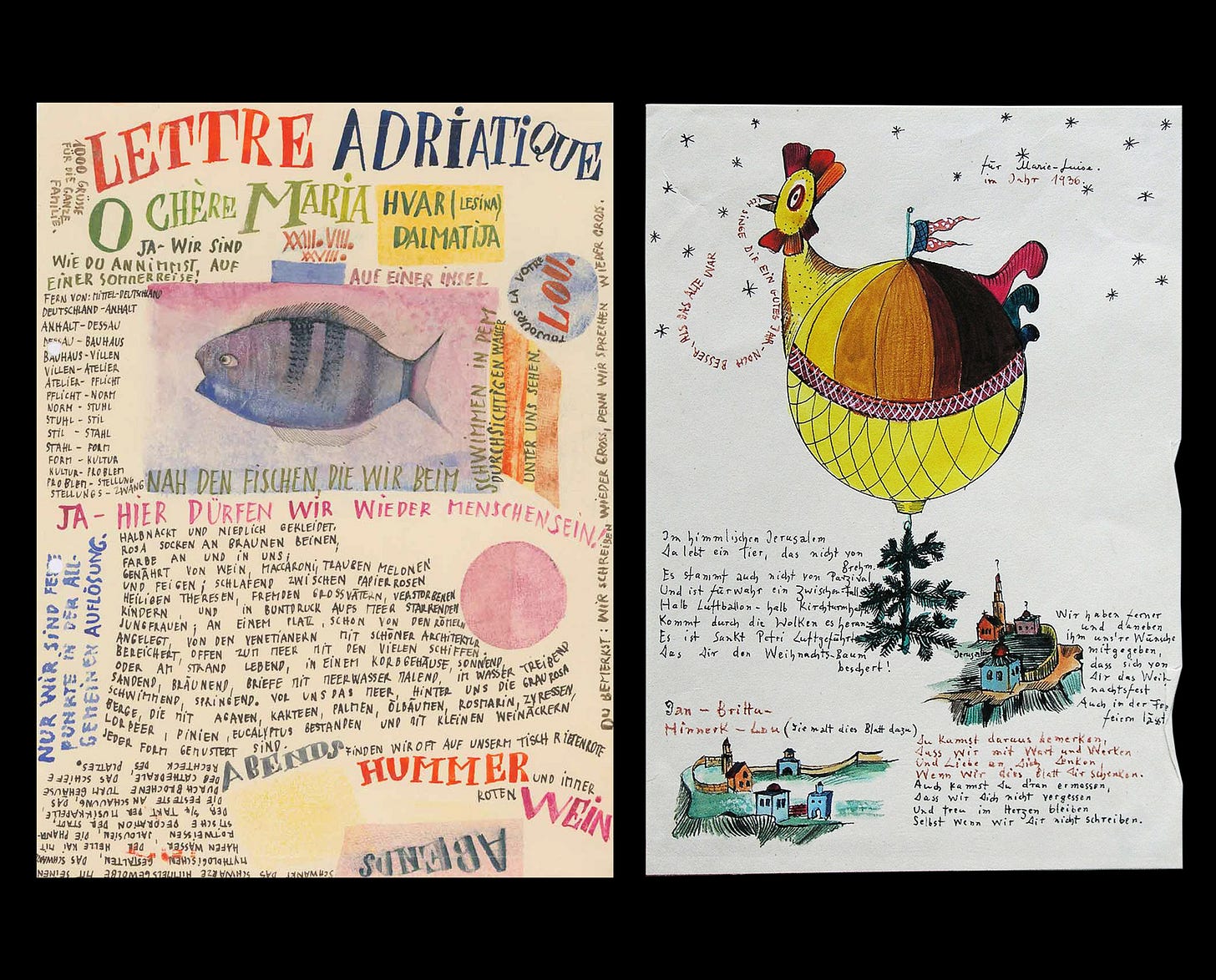

Lou's artistic journey took many turns, including leaving the Bauhaus without a degree to support her husband's freelance career as a mural-color designer after he successfully passed his master’s exam in 1923. As Hinnerk traveled across Germany for work, Lou remained with their first son at her parents' house in Wesel. During this time, she created her enchanting Phantastiken – picture letters combining labyrinthine compositions of images and text.

In 1925, Lou Scheper-Berkenkamp continued her studies and joined Oskar Schlemmer's department of the Bauhaus Stage when her husband accepted Walter Gropius' offer to lead the mural workshop at the new location in Dessau. She worked passionately on Schlemmer's renowned Triadisches Ballet and designed sets and costumes for newly conceptualized Bauhaus dances.

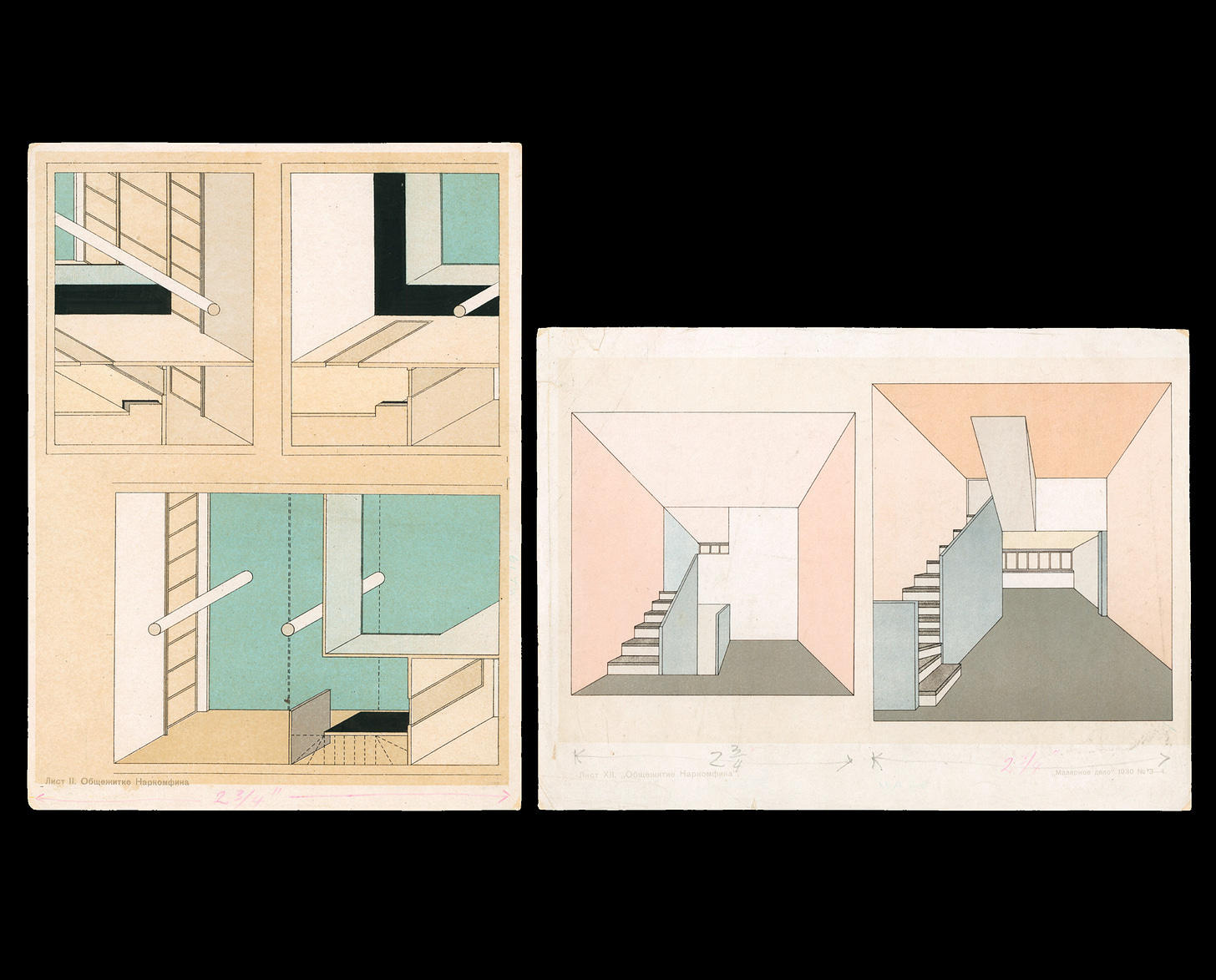

A few years later, in July of 1929, Hinnerk Scheper was invited to Moscow by the Construction Committee of the Supreme Economic Council. Tasked with organizing the establishment of Maljarstroj, a central color advisory agency for the entire Soviet Union. Recognized as a skilled color specialist in modern architecture, Hinnerk was granted a one-year leave from his duties at the Bauhaus. Lou Scheper-Berkenkamp, the supportive partner, accompanied him on this adventure, collaborating with him on essays about architecture and color. Additionally, she showcased her journalistic talent by writing articles for the German-language Moskauer Rundschau newspaper.

The rise of the Nazis and political turbulence ultimately forced the Bauhaus to close, prompting Lou and Hinnerk to follow Mies van der Rohe to Berlin in an unsuccessful attempt to privately continue the Bauhaus. Throughout the war, the family lived in isolation, but once the war was over, Lou returned to her artistic pursuits.

In retrospect, she described the devastating effect of the Nazi era as:

Light-clear and dark-clear tones, pure white and pure black, varied shades of gray without pollution-this was the color world into which the terrible brown, the incendiary red of the Third Reich broke. What lay before 1934 was buried and must be painstakingly brought to light again, brought to consciousness.

She published four children’s books, initially created for her children in the 1930s, and actively contributed to Berlin's cultural resurgence. Lou participated in numerous exhibitions both within Germany and abroad, and was a founding member of the Berlin artists' association Der Ring. After her husband Hinnerk Scheper's sudden death in February 1957, she continued his work in color design for Berlin's architectural landscape. Although her own exhibitions took a back seat, she continued to publish articles on building development and monument preservation, and was involved in various color consultation and design projects. Among her most important projects were the color design for the new Berliner Philharmonie by Hans Scharoun and the new Berliner Staatsbibliothek, although the latter was not implemented before her death in 1976.

II. Die Geschichten von Jan und Jon und von ihrem Lotsen-Fisch

The first draft of Die Geschichten von Jan und Jon und von ihrem Lotsen-Fisch was originally made by Lou in the 1930s for her two children, Jan and Britta, but due to financial and ideological adversity was not published until after World War II. She collaborated with publisher Ernst Wunderlich, who, despite the challenging post-war conditions and censorship regulations imposed by cultural advisory boards, was committed to producing high-quality children’s books. In a letter to Lou Scheper-Berkenkamp, Wunderlich wrote:

"I may express the hope that our emerging joint work may serve the cause of children's books".

The post-war conditions significantly hampered the production of books: paper shortages, irreparable war damage to printing machines, and increasing transportation problems amidst the smoldering East-West conflict hindered the work. The cold winter of 1946/47 in Berlin, which went down in history as the Hunger Winter and was one of the coldest of the 20th century. Temperatures in Berlin plummeted to as low as -20°C (-4°F), and heavy snowfall made living conditions unbearable. Many people resorted to scavenging for food in the streets, while others survived on meager rations distributed by the authorities.

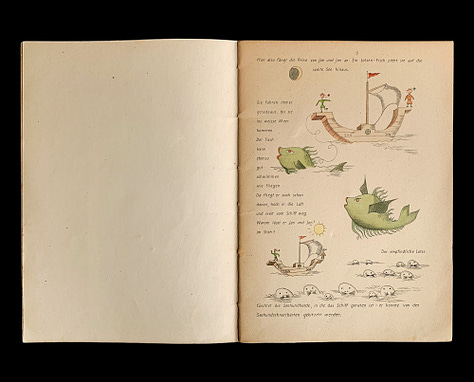

Die Geschichten von Jan und Jon und von ihrem Lotsen-Fisch conveyed a personal concern of Lou Scheper-Berkenkamp by playfully teaching children about good and evil. She emphasized: "One should not be ashamed of the archaic basic concepts". The stories received much praise for their artistic design, proximity to the Bauhaus style, and the unusual combination of humor and fantasy.

However, there were also critics who rejected the surreal elements and unconventional design of the children’s books. They accused the publisher of experimenting for the sake of novelty and claimed that the books might provoke fear in children:

"Children's books should be clear and convey a healthy realism. They should not invoke nightmares."

Despite lively and forceful defense by Scheper-Berkenkamp and Wunderlich, as well as influential supporters like Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius, public opinion could not be swayed. Wunderlich later expressed his disappointment:

"Artistic achievements cannot thrive in such an atmosphere - they require a certain benevolence and an inner readiness that is currently hardly noticeable anywhere in Germany. It turns out that understanding for modern artistic endeavors has been widely destroyed [...] After the tremendous upheavals of the last decades, there is still so much fatigue in the souls."